Abdulaziz reflects on the highlights from serving as a mentor for CEW.

STORIES

Students Speak at University of Alaska and Visit State Legislature

On January 22, 2013, three YES students hosted by AYUSA were invited to speak at the University of Alaska Southeast Rec Center as part of the university’s series on “translocal identities and cultural connections.” The three students, Haytham from Gaza, Maha from Yemen and Abdulla from Bahrain, are currently placed in Alaska. The article below originally appeared in the Juneau Empire and was written by Melissa Griffiths.

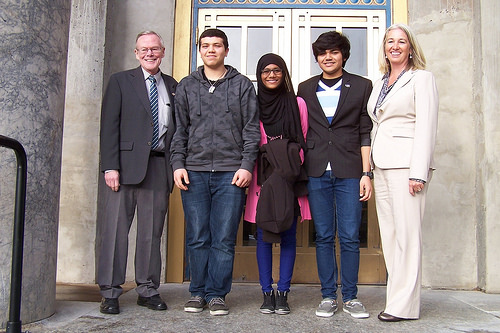

Haytham, Maha and Abdullah were also introduced to the State House of Representatives at the beginning of the session on January 24, 2013. After an opening benediction and pledge of allegiance, Representative Munoz introduced the group. The session was broadcast across the entire state on Gavel to Gavel by the local public broadcasting team. A recording of the session can be seen here.

High school diplomacy: How Muslim Exchange students are changing views

The only thing that made any of the three Muslim exchange students stand out was Màhâ Abdulrâzzàq’s colorful head scarf, or hijab. Otherwise, on the stage were three very normal teens. But that’s the point, really.

The Kennedy-Lugar Youth Exchange and Study (YES) program exists to encourage interaction and understanding between students from predominantly Muslim countries and Americans. In the U.S., less than 1 percent of the population identify as Muslim. Abdulrâzzàq of Yemen, Abdulla Husain of Bahrain and Haytham Mohanna of Gaza are all in the midst of a year-long exchange, placed in Southeast Alaska high schools.

On Wednesday night, the three students took the stage at the University of Alaska Southeast Rec Center as part of the university’s series exploring “translocal identities and cultural connections.” While the focus of the series is mainly geographically the Pacific Rim, and the students hail from the Middle East, Professor Robin Walz pointed out that 44 percent of the world’s Muslim population lives in Asia and immigration to the U.S. is coming more from Asia than other regions these days.

“This is going to be reconfiguring our world, our social and cultural world,” Walz said.

And it could happen in ways most people wouldn’t expect.

Husain expressed frustration that another exchange student would introduce him as her “terrorist friend,” and was unimpressed with a line of questioning that started with, “Would you bomb the United States?” and continued with questions about whether his friends, family or anyone in his entire country might commit a terrorist act.

“No one told me if I am a terrorist, but they just asked, ‘Do Muslims really kill people?’ or ‘Do they really bomb people?,’ but they don’t. This friend, I think she was kind of joking, but it still hurt,” Abdulrâzzàq said.

The students believe this program will help to redefine what people will expect of Muslims.

“Maybe like nine years ago, which was the first year of the program, people think middle eastern people — Yemeni, Bahrainian, Palestine people — they are terrorists, they kill people, but students like us, Muslim students, start to come and they start to know people and stay with the people, they of course change their minds,” Abdulrâzzàq said.

Mohanna was skeptical of how stereotypes are put into place for Middle Eastern people, especially after Sept. 11, 2001, asking the crowd, “How did you know? Media? Did you see the plane? Did you see anybody? ... But if you want to really know about Muslims, their religion, you should go there and meet with them and stay with them.”

It’s not just Americans holding stereotypes against Muslims though. There are misunderstandings on both sides.

Abdulrâzzàq said many Yemeni people hate Americans, viewing them as mean and arrogant.

“Now, you see, as I know that most Arabs hate Americans — why? Because they think that Americans hate Arabs. And 9/11 is the biggest thing, that Americans think that Arabs did that,” Mohanna said. “Now, this exchange program makes really good effect in changing minds and ideas from Americans.”

If the stereotype is that all Arabs hate all Americans or that all Muslims are terrorists, these students prove otherwise. But stereotypes weren’t all the students talked about. They mostly focused their presentation on positive experiences. Like snow.

For each of the students, it was their first snow. And snow and ice were all they and their families pictured for Alaska. Each recounted a feeling of shock at being placed in Alaska, and recalled family members suggesting they didn’t really have to go if they didn’t want to.

Mohanna said he at first tried to reject his placement in Haines, but the organization encouraged him to stick with it. Abdulrâzzàq said she was excited when she saw the photo of where she would stay, not initially realizing the sunny yard was located in Alaska; her brother had to help convince their father to let her go and that she wouldn’t be living in an igloo. Husain’s older brother was apparently upset when he found out his younger brother had been accepted to the program when he had not been. His dad had initially wanted to pull him out of the program.

All three were determined to spend a year in America, though. And once they were able to obtain visas, which isn’t always easy (wait times varied from a week to a month for these students, though some reported friends having to wait longer), off they went to a place without igloos, but enough snow to write home about.

Despite the occasional frustrating questions or comments, the three said they’d miss the nice people they met here in Alaska. And the snow.

“I could get used to this weather,” Husain said.

Alaskans would likely wilt in the temperatures the students said were common back home. A nice summer day in Juneau is the equivalent of the coldest winter day in Bahrain, which would explain Husain wearing a jacket in Juneau’s balmy weather.

And what did they miss about home? Yemeni food, Abdulrâzzàq said. The feeling of entering an air conditioned house from the heat, Husain said. My country, Mohanna said.

Family didn’t really make the list, perhaps because of today’s technology. Husain said sometimes he’d start to feel homesick, but when he’d Skype his mom she’d get on his nerves. Another reminder that teens are teens, regardless of homeland or faith.

Family dynamics were in some ways the same; some ways different. Mohanna said he comes from a middle class family with an engineer father and a dentist mother, but his country’s history was at least as important to him as his family history, and very much entwined — his grandfather was run out of his home city into another with the occupation of Palestine. Abdulrâzzàq’s father was a soldier and a teacher, her mother’s schooling ended at eighth grade. Husain comes from a mixed family, with a Muslim Turkish father and a Catholic Filipino mother, which makes for some tense dynamics both at home and in school.

School dynamics seemed to display more differences, with public schools in the middle eastern countries segregated by sex and a different approach to breaking down subjects. The students also noted that there was less choice in subject matter, and that they would stay seated while teachers would rotate.

Abdulrâzzàq noted that her dress code was more lax here, though she still covers her hair as part of her religious beliefs, and that the public displays of affection and out-in-the-open relationships that are accepted here would not be allowed in Yemen. The students seemed to think it would be fine for male American students to spend a year in their countries, but none of them recommended it for female students, whom they thought might face extreme scrutiny and even harassment.

Mohanna said another difference between home and America was freedom. In America, there aren’t walls. In America, he’s not worried about getting shot.

Facilitating conversations and relationships among middle eastern Muslim students and Americans is just one tiny step toward understanding among cultures, but it’s a step in the right direction. Wednesday’s presentation serves as a good jumping off point for asking questions about how we are alike and how we are different, and how we can break down barriers and achieve peace. What questions are you inspired to seek answers to now?

Article originally published in the Juneau Empire and written by Melissa Griffiths

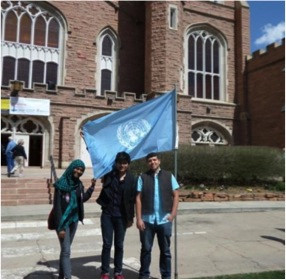

Continuing as Youth Ambassadors

Haytham, Maha and Abdulla have not stopped their activities as youth ambassadors in the U.S. there. From April 7th to 11th, the three YES students attended the 66th Annual Conference on World Affairs at the University of Colorado campus in Boulder. They attended more than a dozen hour and 20 minute long sessions including:

Haytham, Maha and Abdulla have not stopped their activities as youth ambassadors in the U.S. there. From April 7th to 11th, the three YES students attended the 66th Annual Conference on World Affairs at the University of Colorado campus in Boulder. They attended more than a dozen hour and 20 minute long sessions including:

• Negotiating With Iran: An Opening or a Trojan Horse

• Daily Life in Israel and Palestine: In Perpetual Pursuit of the Ordinary

• Collateral Damage: Civilians in War

• Humanitarianism: Handouts and Bootstraps

• A Conversation Among Islamic Women

While in Colorado, Maha and Abdulla also spoke to a fifth grade class at Crest View Elementary School and told their stories to several classrooms at Fairview High School. They engaged in a two-hour long conversation with 25 citizens from Boulder in an event sponsored by the Rocky Mountain Peace and Justice Center and attended the university’s International Festival as well.

While in Colorado, Maha and Abdulla also spoke to a fifth grade class at Crest View Elementary School and told their stories to several classrooms at Fairview High School. They engaged in a two-hour long conversation with 25 citizens from Boulder in an event sponsored by the Rocky Mountain Peace and Justice Center and attended the university’s International Festival as well.

On April 14th, Haytham and his high school art club presented an origami "peacock of peace" to the Alaska State Legislature. "I hope this peacock, which symbolizes the peace, go in each mind and each heart, and really rise our mind about the wars and conflicts,” said Haytham. Read the original story, published on the KTOO website here, as well as the Juneau Empire here.

school art club presented an origami "peacock of peace" to the Alaska State Legislature. "I hope this peacock, which symbolizes the peace, go in each mind and each heart, and really rise our mind about the wars and conflicts,” said Haytham. Read the original story, published on the KTOO website here, as well as the Juneau Empire here.

Photo by Michael Penn of the Juneau Empire